Turnout, Power, and the Missing Link of Civic Education in Uganda’s Electoral Process

Voter turnout is not merely a numerical indicator of participation; it is a political signal.

05 Feb, 2026

Share

Save

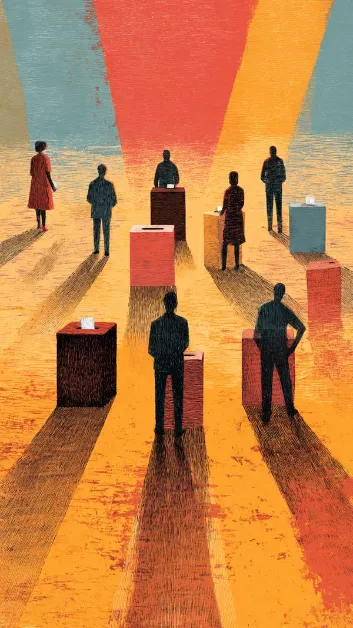

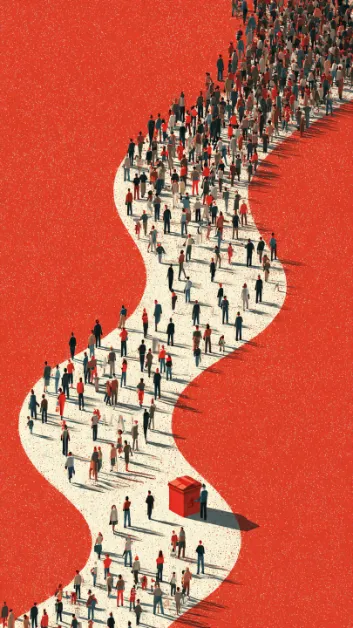

Voter turnout is not merely a numerical indicator of participation; it is a political signal. In Uganda’s recent elections, the strikingly low turnout—particularly in contests for mayors, LC5 chairpersons, and local councillors—reveals a deeper structural problem within the country’s democratic culture. It reflects not apathy alone, but a persistent failure of civic education and a misunderstanding of where administrative power actually lies.

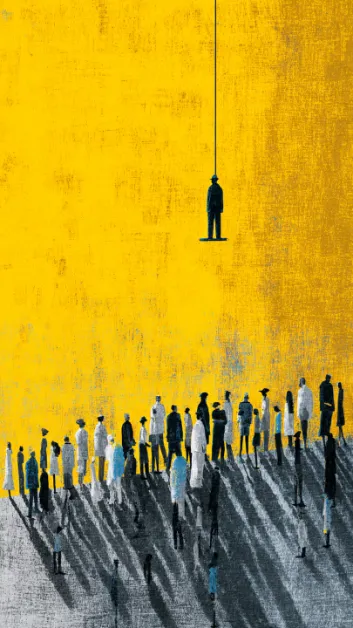

The comparatively high turnout in presidential elections contrasts sharply with the poor participation in local government elections. This imbalance is not accidental. It is driven largely by fear and perception rather than informed civic judgment. For many voters, the presidency is viewed as the sole guarantor of peace and national stability. The act of voting for a president, therefore, becomes an act of risk management—an attempt to avoid the worst—rather than an expression of policy preference or democratic choice.

Local government elections, by contrast, suffer from neglect because voters are insufficiently educated on the roles and powers of these offices. Yet it is precisely these leaders—mayors, LC5 chairpersons, and councillors—who shape the everyday realities of citizens. They oversee service delivery, local infrastructure, education oversight, health systems, land governance, and community development. In practical terms, they are the closest and most consequential representatives of state authority in people’s daily lives.

The low turnout in these elections, therefore, signals a dangerous disconnect between governance and public understanding. When citizens do not know who their real administrative leaders are, democracy becomes centralised in perception and hollowed out in practice. Power appears to reside only at the top, while accountability at the grassroots dissolves.

This imbalance is compounded by the sequencing of elections. Presidential elections dominate political attention, resources, and public imagination, often exhausting voters psychologically, financially, and logistically. By the time local government elections are held, voter fatigue has already set in, and the perceived stakes appear lower—even though, in reality, they are not.

A reconsideration of Uganda’s electoral architecture is therefore necessary. One possible reform would be to reverse the electoral sequence—beginning elections with the lowest local government positions and gradually moving upward to the presidency. Such an approach would ground national politics in local governance and force voters to engage first with the leaders who directly affect their lives.

Alternatively, combining all elections into a single day could reduce fatigue and encourage holistic participation. However, such a reform would demand serious investment in electoral infrastructure, including digitalisation, improved voter management systems, and the recruitment and training of adequate manpower. Without these measures, consolidation could risk logistical failure rather than democratic renewal.

Beyond structural reforms, the central issue remains the role of the Electoral Commission. The Commission’s mandate extends beyond organising polling days; it includes sustained civic education and the promotion of constitutionalism. Civic education should not peak during election seasons and disappear afterwards. It must be continuous, deliberate, and accessible, explaining not only how to vote, but why each vote matters and what each office actually does.

When civic education is weak, fear replaces knowledge. Voters mobilise around personalities rather than institutions, and around survival rather than governance. The result is a democracy that is emotionally charged at the top and empty at the base.

Uganda’s democratic future depends on correcting this imbalance. High presidential turnout alongside low local participation is not a sign of political maturity; it is a warning. A functioning democracy is one in which citizens understand power, distribute their attention accordingly, and hold leaders accountable at every level.

Until voters are educated to see local government elections not as secondary contests but as foundational ones, turnout will remain distorted, and governance will remain centralised in perception. The task ahead is therefore clear: deepen civic education, reform electoral sequencing, invest in capacity, and restore constitutional understanding to the heart of Uganda’s electoral process.

Only then can participation reflect not fear of instability, but confidence in democracy.

About the author

My name is Abeson Alex, a student at St. Lawrence University, whose leadership journey reflects a deep commitment to service, integrity, and community transformation. I have held various leadership positions, including UNSA President of St. Charles Lwanga College Koboko, UNSA District Executive Council Speaker, UNSA Speaker for West Nile, and West Nile Representative to the UNSA National Executive Council. I also served as YCS Section Leader of St. Charles Lwanga College Koboko, YCS Federation Leader for Koboko District, and Koboko YCS Coordinator to the Diocese. In addition, I was a Peace Founder and Security Council Speaker for the peace agreement between St. Charles Lwanga College Koboko and Koboko Town College. I served as Debate Club Chairperson of St. Charles Lwanga College Koboko, District Debate Coordinator, and West Nile Debate Coordinator to the National Debate Council (NDC). All the above were in 2022-2023. My other leadership roles include Chairperson of the Writers and Readers Club, UNSA Representative in the District Youth Council, Students’ Advocate for Reproductive Health, and Students’ GBV Advocate for the District. Within the Church, I served as Chairperson of the Altarservers of Ombaci Chapel, Parish Altarservers Chairperson of Koboko Parish, and Speaker of the Altarservers Ministry in Arua Diocese. Current Positions: Currently, I serve as the Diocesan Altarservers Chairperson of Arua Catholic Diocese, Advisor of the Altarservers Ministry for both Ombaci Chapel and Koboko Parish, and Programs Coordinator of Destined Youth of Christ (DYC-UG). I am also a Finalist in the Global Unites Oratory Competition 2024, the current Debate Club Speaker and President of St. Lawrence University Koboko Students Association. Additionally, I am the Youth Chairperson of Lombe Village, Midia Parish, and Midia Sub-county in koboko district. I am one whose life has been revolving around ensuring that in our imperfections as humans, we can promote transparency, righteousness, and morality to attain perfection. I am inspired by the guiding words: Mobilization, Influence, Engagement, and Advocacy. I share my inspiration across the fields of Relationships, Career, Governance, Faith, Education, Spirituality, Anti-corruption, Environmental Conservation, Business & Self-Reliance, politics , Administration,Financial Literacy, Religion, and Human Rights. Thanks for the encounter.